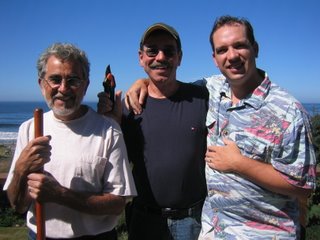

Obituary For Darce Chriss

Workin' man's musician had a gift for healing listeners

Redding Record Searchlight

Thursday, January 17, 2008

Darce Chriss was a true working man in the classical sense, having spent most of his life as a professional truck driver in the Cottonwood area, but he was also an amazing guitar player, singer and bandleader.

He died at his Redding home Nov. 5 at age 78.

Born March 26, 1929 in Oklahoma, Chriss married Margaret Wilson Chriss in 1947 and the union bore three children -- Vickie Cutchen, Rick Chriss and Alana Northern. He had nine grandchildren, three great grandchildren and numerous nieces and nephews in the Redding area. He is also survived by his younger sister Lorraine Norton and her husband Walter. Margaret preceded Chriss in death in 2000.

Chriss took up the guitar as a boy and played with numerous stars like Johnny Paycheck, Merle Haggard and Buck Owens. He also nurtured many musicians in his music room, including Atlantic Records recording artists the Marcy Brothers.

He was a musical healer and he ministered to the north state's senior citizens at community centers between Sacramento and the Oregon border. Seniors would walk into his gigs, but after 15 or 20 minutes, the room was full of 18- and 20-year-olds. Aches would go away, pains would disappear, and spirits would soar. The music rejuvenated and healed; the crowd was reborn.

I first met Chriss in the fall of 2000 at a jam in Shasta Lake. It was late in the afternoon when we got there, and the jam was winding down as the orange afternoon sunlight poured through the windows and flooded the room.

Chriss was playing a solo on his black Stratocaster, the audible tap of his boots keeping time on the floor provided the back beat as the other five electric guitarists provided the rhythm and body of the song. He was backlit and cut an impressive figure with his black cowboy hat. The notes pouring from his guitar were beautiful and soulful as his hand danced up and down the fretboard with a lilting gait.

The music was profound. I was transfixed.

We became musical compatriots shortly thereafter and he invited me to join him at his weekly gigs at the Senior Nutrition Center. I was fortunate enough to play with Chriss intermittently for several years and he was the most giving bandleader for whom I have ever played. He was completely dedicated to his music, which he called "true country," to his band, and to his audience.

One rainy winter morning in 2002, I arrived at a gig to find him in terrible shape.

"I am so sick," he said with a hoarse whisper and watery eyes, "but we can't leave these people without music."

I unloaded the van and set up the equipment while he tried to nurse himself with a cup of tea. As we tuned up, his hearing aids began feeding back into the PA system and the sound was a terrible mess. We scrambled around turning dials and readjusting speakers, but no matter what we did the noise persisted faintly, just loud enough to drive you insane. We soldiered on though, because there was a crowd to entertain.

The terrible high-pitched feedback swelled with the music as we played the first few songs and the sound of the torrential rain on the roof of the building was nearly drowning out the rest of our sound.

However, as we launched into “Blue Eyes Crying In The Rain,” the rain began to subside. As Chriss soloed on his pedal steel guitar, the feedback became harmonic and eerily beautiful. He glanced over at me with a big smile on his face and continued digging into the song, playing a hauntingly evocative, angelic lead. Something magical had just clicked; someone else was in control.

The sun shined for the rest of the gig and the two of us were unstoppable. We could do no wrong and the crowd was delighted. As we loaded up the van at the end of the gig, I was filled with pride to have made such beautiful music against such long odds.

I mentioned that the sun came out just as the feedback went away. “If you care about it enough when you make it,” Darce explained, “music can do just about anything.”

[+/-] read/hide this post